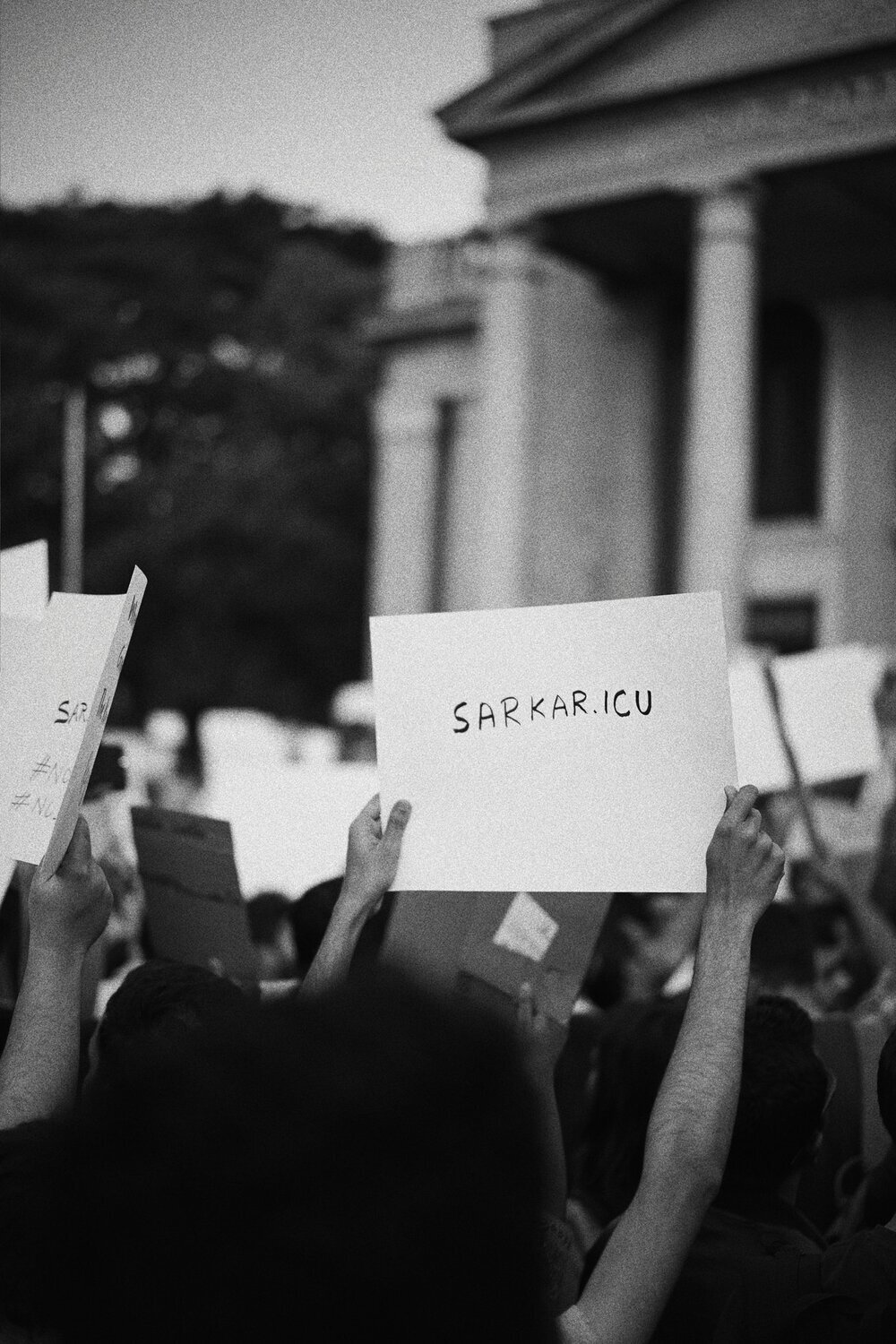

Bangalore Townhall. Image credits: @krngrvr09

Bangalore Townhall. Image credits: @krngrvr09

My cab was stuck in an excruciating traffic jam, quite typical of Bangalore, when I saw them - emerging as a collective, equipped with banners, microphones and raging energy. I grabbed my poster, hurled cash at the cab driver and jumped out before he could return my change. They stood and chanted and listened and waited. In a matter of 30 minutes, the entire 250 metres leading up to the Townhall was packed.

The protest felt like something inherently beautiful articulating itself, even if its contours weren’t defined just yet. It was more than the 200 people arrested earlier that morning at the same protest, beyond the swarm of new bodies gathering in the same place of arrest, all over again, and beyond the short bursts of language picked up into loud chants. The protest was the tearful beauty of hum leke rahenge, aazadi !, and also the hour and a half it took most of us to get there. It was in the uncertainty of where we were headed, the Instagram story we uploaded and our fear of being arrested: the protest began everywhere. It was my friend struggling to spot me even though we were in the same crowd. It was men making sure other men weren’t crowding upon the women, making sure the sanctity of our space wasn’t violated, not even accidentally. With every fervent call and response, the protest kept becoming.

Eventually the police arrived, and the first line of protesters adorned the Indian national flag in defense as if to say: this protest is not anti-national. My section of the crowd couldn’t hear the exchange between them and the protesters, so we just waited, half expecting it to get violent, half hoping it wouldn’t. I did not imagine marches being conducted with the constant uncertainty of direction and location. When I looked around I saw an endless crowd of bodies and realized there were multiple sections just like mine- wondering if they were in the right place, looking for a central axis, and waiting to be told what to do. When the police thronged into the crowd of protesters, you could feel the vapid multiplication of molecules; fear vibrated and resonated between strangers. Against the police, we were a collective.

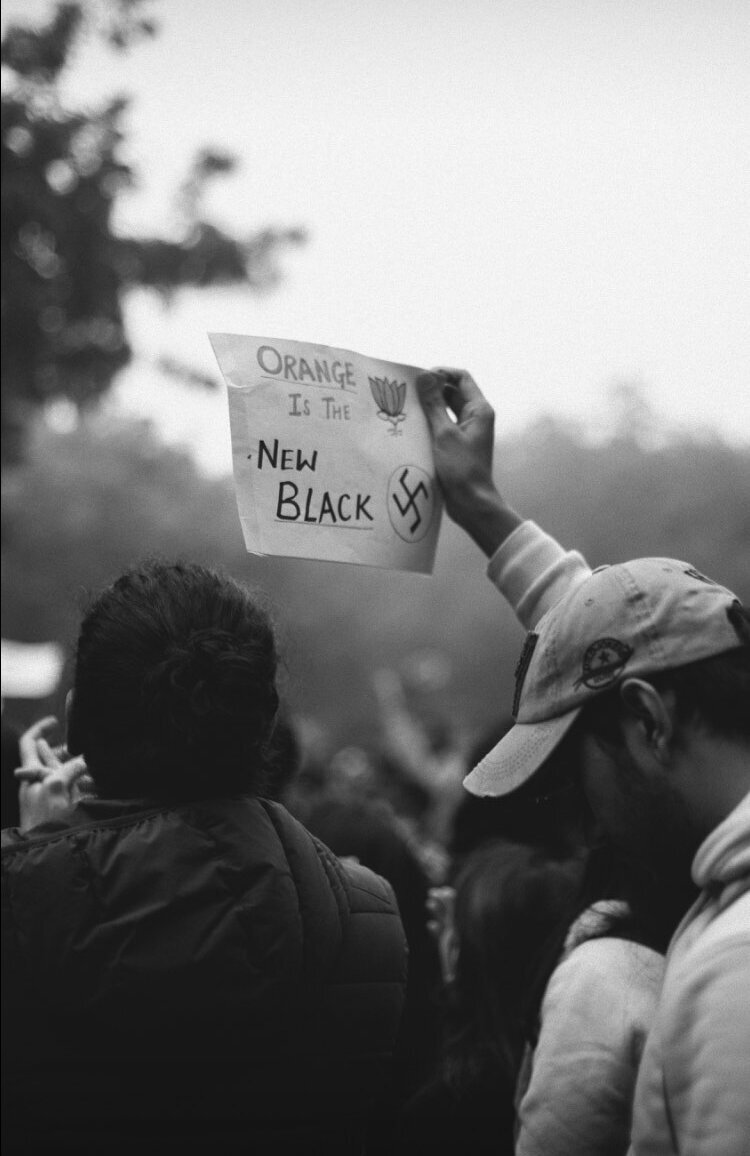

What does collective angst mean? For some, it means delving into political dissent without being branded anti-national. For others, it means a better economy and a functional social system. Today it meant opposing a blatant incursion on the secular fabric of India. A week before the protests started, the Citizenship Amendment Bill became an enforceable law. Read with the National Register of Citizens it meant that only Muslims would have to prove their citizenship and ancestry through ambiguous documents; it meant 200 million citizens being potentially stripped of their nationality un-democratically. I have to keep my stomach from turning at the seeming neutrality in the legal prose; resist the fear of all the blood that may come between enactment and implementation; resist the idea that this- blatant hatred of minorities, detention centres, rapid internet shut-offs & police brutality - this could all be normal one day.

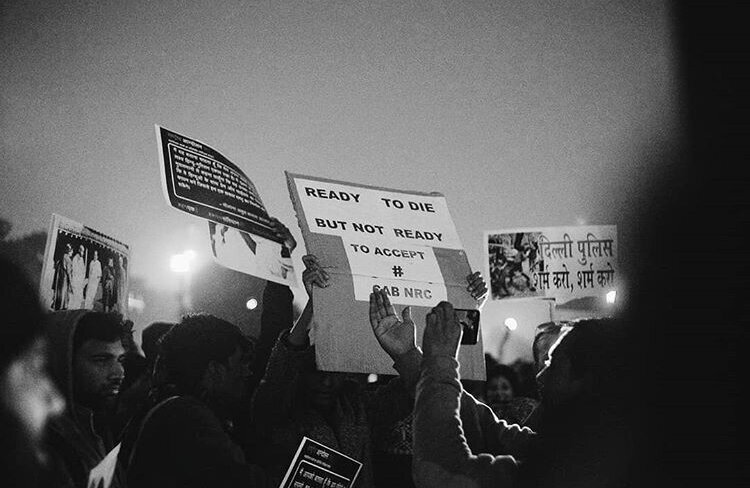

The aftermath of the act led to nationwide protests, activists being detained, professors being assaulted and students being shot at. Within a week, my Instagram blew up with venues and timings for city-wise protests. The days preceding and following the march were a waking nightmare of police brutality. Section 144 was declared just as peaceful protests were getting planned, and yet, hundreds gathered to defy an active governmental order to not do precisely that*,* not because we weren’t scared of repercussions but because we were, we were so scared of dissent, that the presence of this collective fear had now turned into anger.

At the Townhall, empty police buses stationed around us and barricades were readied as the cops attentively looked on to a peaceful crowd seating themselves on the road. The night before, a group of law students were detained for holding candlelight protests against the imposition of Section 144. What was an obstacle deliberately placed to keep us from protesting had now become a part of the protest.

To me, these protests signal a wondrous concoction of righteous anger and secular empathy, they signal how urgent this march is, and how late we have arrived to it. Between hurried print outs of tweets and the confusion in time, place and method - the march was nervous and angry and disorganized. And yet, when the crowd suddenly broke into a song, hogi shaanti chaaron oor ek din, a high tide of hope washed by us. Suddenly, we were marching towards the Townhall as the crowd shouted nyaya! in rhythm. We walked past bystanders on the pavement and people photographing us from their balconies with clothes drying out front. The pillars of the Townhall felt majestic and indifferent in front of us, even as bodies swarmed the roads and steps that lead up to it. Hamaare ghar mein gandagi nahi phailaane denge shouts a woman into the microphone as we seat ourselves on the road, hard concrete biting into our knees and ankles. The sun comes and goes, a police officer approaches her and pleads with the protesters to disperse. We stayed.

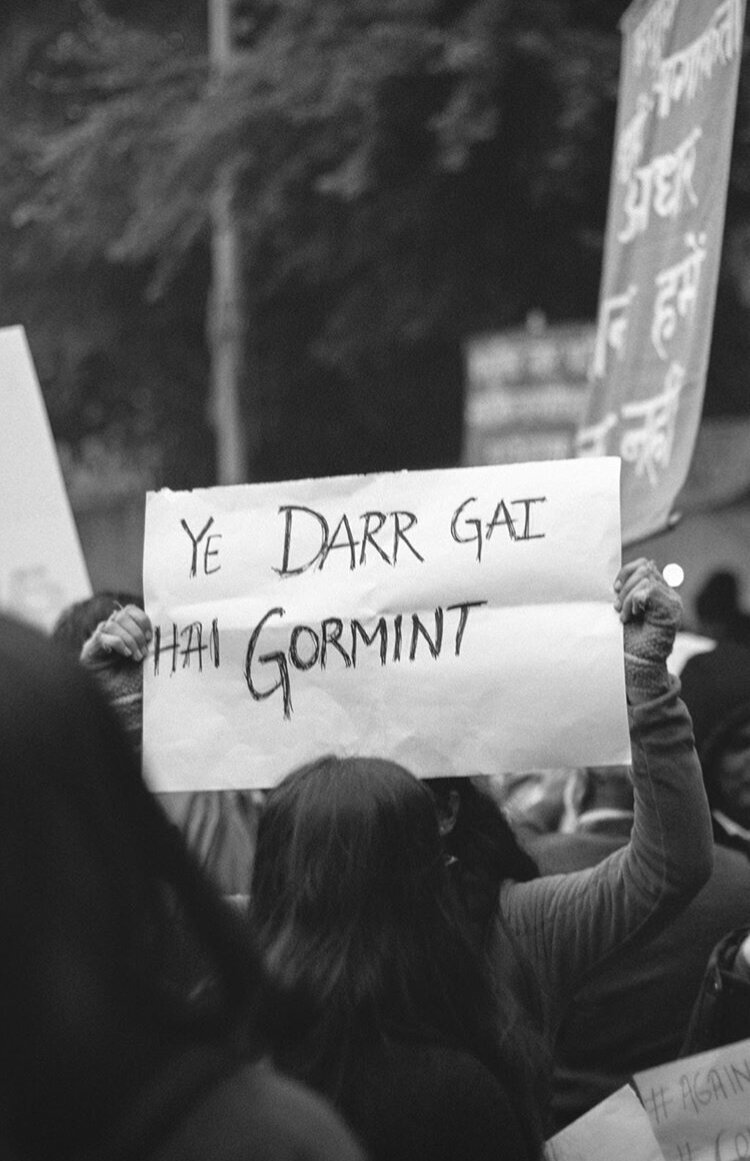

People embraced each other as food and water was passed around. Banners swam across the mass and I was thoroughly amused by them. One said kisi ke baap ka hindustaan thodi hai, another said Secular Republic, not Hindu Rashtra. A man with a hipster man-bun held one that simply said I’m upset. Mine was a copy of the Preamble which I hurriedly stained with red lip gloss in the cab. So bad, even the privileged are here. Eat faeces, fascists. I saw the prime minister’s face next to Hitler’s in at least four banners; a photo of Marie Kondo saying this government doesn’t spark joy, and another saying I’d rather die than accept CAA + NRC. These signs- cardboard, chart paper, A4 printouts - were funny, joyous and fearless. But more than the police, the media, and the politicians, the signs were for us.

Scenes from protests in other cities in India. Image credits: https://www.instagram.com/stories/highlights/17856138556686290/

The march to the Townhall was slow and haphazard and it stalled often. I later learnt that somewhere, women circled men to protect them from arrests, and somewhere else, men circled women to enable safe movement. Everybody was protecting each other because everybody’s safety was at stake. We knew how lucky we were to not have met the same fate as the students in Jamia, or the people in Kashmir and Assam. Mumbai, Chennai and Hyderabad saw similar peaceful protests. In a different city, two students were shot in protests quite like the one I attended. The police wasn’t politely requesting dispersion there, it was charging lathis and launching tear gas shells and bullets. On my way to the protest, I spoke to two lawyers and had multiple friends track my location; I prepped first aid, pepper spray, mini food bars, and water. I thought my over preparedness would inundate me from fear, but it didn’t. You couldn’t tell if I was preparing to attend the protest or flee it.

There were more phones out than banners. People were recording, taking pictures, documenting every part of their presence. This is a typical millennial habit, one we get a lot of flack for, but today I associate no scorn with it. Recording a protest is marking your presence in it, and perhaps without that marker, we wouldn’t be protesting at all. With the government actively shutting down internet access in Kashmir, Assam, UP and parts of Delhi for protests, taking a picture at the protest isn’t just pay off for activism - it is activism.

The revolution may not be televised, but it will be retweeted and reposted.

I wish I could say I was the loudest voice in the crowd, or the first one to be detained, or the first one to call out a rotten political conscience. Truth is, by the time I spoke up, my narrative was merely reaffirming an already brimming vessel of anger - I spoke neither to cajole that anger nor stir it. This is why privilege is such a complex and relative thing.

At the march, our collective sum did not signify homogeneity. I was quietly specifying the crowd into Muslims and Hindus, denim-clad and kurta-clad, women and men. I wasn’t the loudest voice because I didn’t need to be, my presence at a protest does not inoculate me from my Hindu privilege, just as my Hindu privilege does not protect me from the lack of safety afforded to a woman in this country. The stakes are always higher for someone else. The CAA doesn’t just target Muslims and dissenters; it threatens multiple marginalized communities: the poor, the indigenous, the tribal and the trans.

This is not to say that privilege signifies immersion in self-pity, but that privilege itself cannot be free of self-critique and self-awareness. This is to also say that the naive optimism of “secularism” in our constitutional preamble looks very complicated on ground. Privilege leaves room for indifference and false equivalencies. It often makes a lot of us myopic and apolitical.

A reporter asked protesters about their technical views on the CAA and NRC. I wonder if it’s ever possible to arrive at fundamentally divisive issues like these in an impartial manner. To me, political antipathy is like travelling to the opposite end of your intellectual spectrum and burying yourself there.

In the last ten minutes before I reached the protest, I fielded multiple back to back calls from my matriarch mother, who was furious about me skipping office to risk imprisonment (her words, not mine). Her fear is not irrational: she belongs to a generation tasked with economically bettering a family, paying taxes and school fees and mortgages, and hoping it all accumulates into a deterministic-ally stable life. A paycheck has proof of concept, a protest doesn’t. She is not wrong. My mother cannot reconcile with my beliefs but that does not mean I am not her. She and I, we are women bound by the same generational thread of responsibility, even if she is more concerned with self-preservation than identity politics. We are the same because each one of us considers the other radical, naive, and misguided.

The march was badly planned and disrupted; it was full of flawed execution, unlearnt slogans, and tired people. But the march happened, here and everywhere in this country. That matters. Without the march- there’d be a blank apolitical vacuum where collective activism needs to be. If the march hadn’t happened, if we too had our internet cut off, we’d all be singular, isolated vessels of despair and disbelief.

The truth about millennial activism is that it may start small on phone screens, but collectively, it is infinite. It’s filled with small acts of resistance and boring acts of preparation. What snacks to take? what do I tell my boss? what’s your ETA? should I retweet this? what if nobody shows up? what if an entire minority is swept into a detention center one day and nobody protests at all?

It’s asking big questions about identities, and small ones about itineraries.

It’s confusing and imperfect and messy - but the mess isn’t a fault, its magnificence.

My activism always felt inadequate and apathetic to me, but on my walk back home I realized my activism doesn’t need to be perfect, it just needs to start somewhere. Sitting on a hot road with no cell connectivity and being surrounded by hundreds of people, each wondering when we’ll move- that felt like a start. As I write this in its aftermath, the march is something mystical and glorious. I have to strain my memory to remember the scratches in logistics or the probable repercussions. That is because the words spoken at the march were deep, glorious and human. They reverberated through every cell in everybody present there. You could feel democracy step out of our constitution books and show up in person - precious and fragile and desperately in need of preservation.

When I heard my own voice chant aazaadi with the crowd, I felt the cathartic fullness of crowd sourced activism.

When we marched, we weren’t on a standard itinerary, and nobody was sure of where the march was going, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t happening. Rerouting venues and recalibrating slogans and retaking pictures: we were the march, and the march was us.

Image credits: @FaizanSiddiqKha

Image credits: @FaizanSiddiqKha

Note: The protest attended by the author took place on 19th of December 2019.

Images sourced from Twitter, Instagram.

Here are a few materials to refer to, for technical information on the CAA + NRC, as well as news articles pertaining to the incidents mentioned:

http://164.100.47.4/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/370_2019_LS_Eng.pdf

http://prsindia.org/billtrack/citizenship-amendment-bill-2019

15 questions on the CAA and the NRC

https://www.altnews.in/pm-modis-speech-on-caa-nrc-a-combination-of-falsehoods-and-half-truths/